18 Sep Same Problems, Different You: Life After Clip Charts Post 3

In C

Eh, maybe in our dreams.

The best/worst part of classroom communities is that they are ever evolving. New kinds of classwork enter the picture, friendships dissolve, families go through tough patches, we start losing sleep and eating bags of baby carrots instead of lunches with protein because its easier. Each element crashes into the next in the intimate ecosystem of a classroom. Ollie’s tough night of sleep causes him to be shorter with Myra, Myra’s hurt feelings cause her to curl into herself and refuse to move off the rug, this refusal adds to a feeling of frustration I am already having with Sammy forgetting their field trip form for the third day in a row and before I realize it I have declared that no one will ever get recess again for the rest of the school year because it is taking too long to clean up.

Not that this has ever happened to us. *Clears throat, looks shiftily from side to side*

So this post is about the problems you will have, I will have, we will have, and building a proactive plan to address them. How we wish we could say, “Do this one thing and all will be solved.” but that is not human relationships work. So please, remember as you read our suggestions that you know your children best, and that our language may not be your language, and that the most powerful tool you have is the warmth you demonstrate for your children each and every day.

So let’s get into it, shall we, lets take a close look at one predictable problem:

Work Refusal:

Oooooooweeeeeee! If there is ever an issue that can get under a teacher’s skin it is this one. Maybe it is refusing to finish a math problem, open that writing folder, or come to the rug, but at some point a child is going to tell you “no.”

Give yourself a minute here. This can feel so frustrating to us as teachers. We know that the work will ultimately help the child, we have the best intentions at heart, and yet, there is that “no”. We might feel any range of feelings, from confusion to annoyance to hopelessness to fury. We need to work through and process and study those feelings… later, maybe over french fries covered in cheese. Right now we need to make some decisions.

First things first, believe whole heartedly there is a logical and meaningful reason to the work refusal. Maybe the child is all burned out (see more about willpower depletion in Kids First), maybe the work does not make sense to the child and they are worried about failing, maybe the child is confused and not sure how to tell you. Maybe the work only seems fun to you, the adult (solving a math problem with candy you aren’t supposed to eat, for example). Maybe the child has some very real concerns and needs we do not know about: hunger, fatigue, fear, fighting family members, mom away on a work trip. What usually doesn’t work is threats and pleading, they tend to escalate an already fraught emotional exchange.

If a child is refusing to work because they are burned out by the work, no amount of taking recess or threatening choice time will give the child back the energy they need to complete the work. Research shows us that will actually compound the problem.

No amount of cajoling can overcome a fear of failure.

Sometimes the only way children can feel that they have control in chaotic environments is by asserting their right to say no. (And by having that no be heard)

So what gets us out of this situation?

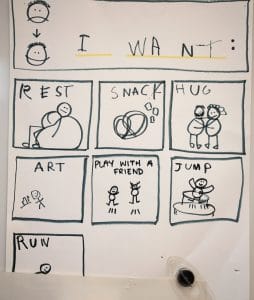

What if when a child said “NO” to our request, we said, “Okay, that is your choice. What will you do instead to help your brain grow?” or “Take a look at the schedule and let me know sometimes when it might make sense for us to meet and figure out a plan to get this done.” What if start from the assumption that children know their needs best?

We are not suggesting that children who refuse work not do any school work, but that we ask ourselves to assume that refusal comes from a place of self-knowledge, and that we can come to a mutually agreed upon solution.

In Other Words:

Confronting work refusal is similar to tackling any classroom issue.

Name and accept what the child has said, “It sounds like you are saying that you do not want to work on your writing because it’s boring. Is that right?” Gather more information by asking open ended questions, “Can you tell me more about that?”

Make a coaching call, that is, with the information you have, ask yourself the following questions to determine if this is something you are going to talk through now, or pause your interactions and come back to it when you are both in a better mental space.

- Where is the child emotionally?

- Where am I emotionally?

- Does this child see me as reliable and trustworthy?

- Does the child feel capable?

- How important is THIS work compared to the long term work the child needs to do

Suggest a compromise, value the child’s input, outline the terms clearly. Letting the child know you hear them, and you are valuing their thoughts does not mean you step away from the expectations you have set that everyone is a learner.

- Could the child have a timer and spend some time working and some time on a break?

- Could the child do something different and achieve the same goals (e.g. work on narrative writing in the form of a comic book, work with a partner, etc)?

- Could the child work at a different time?

Follow through on the short term plan and start making long term plans. Work refusal, and all similar challenges, are at times a one time deal, but oftentimes are longer, bigger knots to untangle. If its a child’s feeling of capability, trusting their ability to make decisions will help, but they may also need some strategic instruction from me. If it is a scheduling or curriculum issue, then I may need to rework my daily schedule or think through how to make the work more flexible and choice oriented for kids.

The “But What If” Section

-

- But what if the child won’t talk to me to make a plan? Walk away and give the child space. Come back to it and keep trying until the child is ready to talk.

- But what if all the other kids see this child doing something different and start saying “no” to work? Probably, then, the work you are asking kids to do is not challenging or engaging enough. That may sound harsh but often times the work we ask kids to do does not ask lots of them intellectually or creatively. It could be that you need to have a quick conversation about how everyone needs different things to learn, but if no one wants to do that thing you have planned, the thing may not be so great.

- But what if no one listens to me anymore because I am not acting like the boss? The ability to compromise is a better show of your comfort in leadership than the dictator-like demand that you MUST do this thing NOW. Compromising is not weakness, it is what we want of all leaders.

- But what if the child never does the work? Is this the only day they will ever be in school? No. Have you ever skipped a workout? You don’t go back when you beat yourself up for missing it. When you have self compassion, that’s when you say, “Okay, I can do it now.” Same for kiddos, except we will model compassion. “Its okay that we did not get this figured out right now, but we will revisit it at ___ time.”

So how are things going for you? We’ve heard so many stories of teachers setting aside their clip charts and old systems of behavior management in favor of a new way of thinking about community building and keeping children at the center of everything we do. If you give some of these strategies and protocols a try, let us know how they go. What’s working for you and your class? What’s still challenging? Send us a message via our websites- kristimraz.com and christinehertz.com. We’ll celebrate the successes and try to help problem solve the messy bits.

We know the road can be a bit rocky, but we’re so honored to be traveling it with you and excited for what could be.

Matthew Wright

Posted at 20:46h, 18 SeptemberBut What If…. their future boss (or even teachers for that matter) does not show them the same understanding and flexibility when they refuse to complete a task? Are we setting students up for failure in the future when they expect others to be as accommodating, but they aren’t?

kristimraz

Posted at 09:50h, 27 November1. I think we worry too much about what’s next instead of thinking what the child needs now.

2. It’s not about never finishing a task, as much as it is helping children build capacity to face difficulty and challenge over time.

3. The goal is that we help children move past refusal, but taking away everything under the sun is not a strategy

Pingback:Student Agency: 5 Steps for Beginners – HonorsGradU

Posted at 09:54h, 16 November[…] Get to the root of defiant behavior, and find new strategies to address it. “Life After Clip Charts” series gives excellent strategies that can replace those clip charts and stickers. They […]

Pingback:Instead of Putting Fuzzies in a Jar, What If… – HonorsGradU

Posted at 17:58h, 11 January[…] …we work to move away from collective punishments altogether, which can discourage individual students from doing their best (see Life After Clip Charts series)? […]