15 Nov Thinking About Language Development

One big puzzle I have been sitting with these days (along with some very smart thinking teachers) is teasing out the fluctuating dynamic of a child’s language development and literacy development. When I first started teaching, I often diagnosed a child’s emerging language skills as reading difficulties.

One big puzzle I have been sitting with these days (along with some very smart thinking teachers) is teasing out the fluctuating dynamic of a child’s language development and literacy development. When I first started teaching, I often diagnosed a child’s emerging language skills as reading difficulties.

Here is one example.

A child would hold a book that said, “I see the black dog.” and the child might say, “I see black dog.” Hmm, I would say, that child needs 1-1 match, or that child doesn’t know the sight word “the”.

Here is another example.

A child might miss many endings to words on their assessment. On first glance it appears that the child needs to work on reading through the whole word. But on closer study, the endings are all on verbs with -ed. Need, not needed, help, not helped.

In both those cases I set about teaching reading strategies, while ignoring the real dynamic in play. Reading, especially early pattern books, assumes children have spent many many many days and weeks and months and years being immersed in the same kind of English we use in school, and therefore can count on that innate knowledge to help them figure out the books in front of them. That is not the case for all children, including those who have English as a first language.

The way readers who have been immersed in the same kind of English that is used in school negotiate things like the word “the” or the endings on words is by knowing deep in their language wiring how the words should sound when spoken. Sure they may check in with the visual end, but the language structure is the driving force.

Not every reader using A-C texts can identify the sight word the, while still reading it correctly.

Not every reader holding an F book is looking through the whole word to add the -ed.

To put it another way, if I do not yet use articles in speech (words like “the” and “a”) why on earth would I assume they are in a book? That doesn’t mean I don’t have 1-1 match, it means the scaffold is a mis-match for my own language development. And If I do not yet have mastery over how words in the past tense might sound, it won’t strike me as odd to to say the words “She brush her hair” out loud, but it also doesn’t mean I don’t know how to use the end of the word.

If I only look at the reading side of this (memorize a million sight words, read through to the end of every word) I am working on the pipes and not the well from which the water comes. Oral language drives reading and writing and much of my learning life. So how do I set about helping kids learn more about school English without getting overwhelmed myself?

Before I go any further, I must give a ALL OF THE credit to the people who have taught me all of the things I am about to share: first up, Enid Martinez, I had the pleasure of learning from this amazing teacher and staff developer at the Reading and Writing Project where she taught me so much about the development of language. Amanda Hartman, too, was instrumental in teaching me the connection between the teaching structures we use every day, like shared reading, and the implicit language instruction we could make more explicit. And Yvonne Yiu, a truly gifted ELL teacher that I had the pleasure of getting to know when we worked together at PS 59, nudged my teaching in a billion ways. I hope I have not neglected to mention anyone here, if I have I will make sure I correct it.

Okay onto the work.

So teaching into language and not just reading can sound somewhat daunting. When? How? What? So here are some of the things I learned from these wise folks, that you might want to try too.

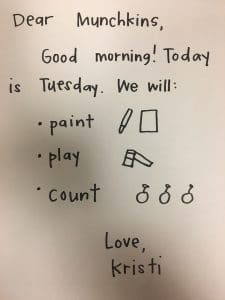

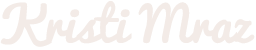

Morning Message

past and reread as a way to reflect what happened during the day. This is a truly contextualized way to understand how words sound and look different to indicate time.

Shared Reading

Shared reading is a great place to play with vocabulary and tenses, and also to key children in to common book language structures. Enid taught me to draw children’s attention to this by referring to how the shared reading book “will talk”. For example, even before we look at the words we might say, “This books talks like it is giving us directions, it sounds like In goes the mouse. Let’s practice how that sounds… in goes the” . This kind of preview isn’t about teaching sight words, its teaching that some words go together. When I see “In goes” I start to anticipate “the”.

Guided Reading

Enid was also the source of an incredibly helpful tip for my book introductions. If you can, give the introduction in the tense of the book. Don’t introduce extra vocabulary or a whole different sentence structure. Just speaking in the tense of the book can give children a boost on the structures they should anticipate. I cannot tell you how many book introductions I have given that sound like this, “This book is about how kids go to school. They go in a car or a bus, etc” Then the child opens to the first page, where it says, “I went to school on a bus” and the kid says, “I go to school on a bus.” Why? Because I just set them up for that with my language model. A simple switch of: “ This book is about how children went to school.” implicitly supports using structure as a source of support.

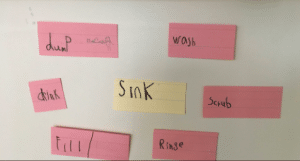

Interactive Writing

As teacher of young children, it is in me to make interactive labels for everything. If it existed in our space, we made a label for it. Amanda pointed out to me once that every label was, in fact, a noun. Why not label with verbs we might use in those same spaces? This was particularly handy in advance of the How-To unit when specific vocabulary becomes a big conversation, but also helped us think as a community about becoming more specific in our words. This picture comes from the classroom of Hannah Huhr, a first grade teacher in NYC.

Word Study

Word study often ended up just being a study of spelling features and sight words in my room, which was missing a huge opportunity to dig a little deeper into the actual STUDY of words. Beyond new vocabulary, we could think long and hard about why those endings mattered so much in our conversation and in our reading and in our writing.

We sorted again by ending sound.

We played “defend your end” where children matched the ending sound to the picture and had to explain how they new it was a match. Eg: This one has “ed” because it already happened. The card at the top that is cut-off in the middle picture says “he/she/they”. To honor all children and their identities, we aim to stay away from the binary he/she. Yes, “They jumps” is historically grammatically incorrect, but a language is fluid and changeable and political. Technically we should also be using the word “shall” a lot more than we do but who is actually upset about that?

Play Workshop

Honestly, the question is really how are you NOT working on language when kids are playing? The language structures of asking to play, asking for items, giving feedback, the content specific vocabulary to play things like family, naming items in the classroom more specifically so children cam move beyond asking for “that”. I could write a whole book about it, but my lovely colleagues Alison Porcelli and Cheryl Tyler already did.

Alright.

You made it to the end. It was a doozy, but hopefully a good one! Share your own ways of integrating language learning into your packed day! There are loads more ways, and one of the best resources I can point you to is this one.

Loralee Druart

Posted at 01:14h, 21 NovemberThank you. We learn wonderful things from you (and those you learn from).